Update (9/20): I guessed the species correctly: all the Large Flute Players.

Update (9/24): I neglected to note that there’s another paper out there by Young June Lee called Description of three new genera, Paratibicen, Megatibicen, and Ameritibicen, of Cryptotympanini (Hemiptera: Cicadidae) and a key to their species. Link to it here. This manuscript goes beyond one new genus, and instead introduces three: Paratibicen, Megatibicen, and Ameritibicen. Lee’s paper differs from Sanborn & Heath in that the large Neotibicen are spit into Megatibicen and Ameritibicen in Young’s document, but they’re all Megatibicen in Sanborn & Heath’s paper.

Last night I had a rough night’s sleep. I tossed and turned all night long. I remember looking at the clock and seeing 4 am, and thinking “tomorrow is ruined”. Sometime during the night I dreamt of finding thousands of molted Neotibicen exuvia clinging to shrubbery — a rare if not impossible sight in real life.

When I woke I checked my email and found a communication from David Marshall. David is well known and respected in the cicada world for many things including describing the 7th species of Magicicada with John Cooley, as well as being part of the team who defined the Neotibicen and Hadoa genera (link to paper)1.

David wrote to let me know that Allen F. Sanborn and Maxine S. Heath had published a new paper titled: Megatibicen n. gen., a new North American cicada genus (Hemiptera: Cicadidae: Cicadinae: Cryptotympanini), 2016, Zootaxa Vol 4168, No 3.(link).

So, what is MEGATIBICEN? Assumptions after the abstract.

Here is the abstract:

The genus Tibicen has had a confusing history (see summary in Boulard and Puissant 2014; Marshall and Hill 2014; Sanborn 2014). Boulard and his colleague (Boulard 1984; 1988; 1997; 2001; 2003; Boulard and Puissant 2013; 2014; 2015) have argued for the suppression of Tibicen and the taxa derivatived from it in favor of Lyristes Horváth. Boulard’s argument for suppression was first described in Melville and Sims (1984) who presented the case for suppression to the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature with further comments made by Hamilton (1985), Boulard (1985), and Lauterer (1985). A lack of action resulted in additional comments being published in 2014 again supporting the retention (Sanborn 2014; Marshall and Hill 2014) or the suppression (Boulard and Puissant 2014) of Tibicen.

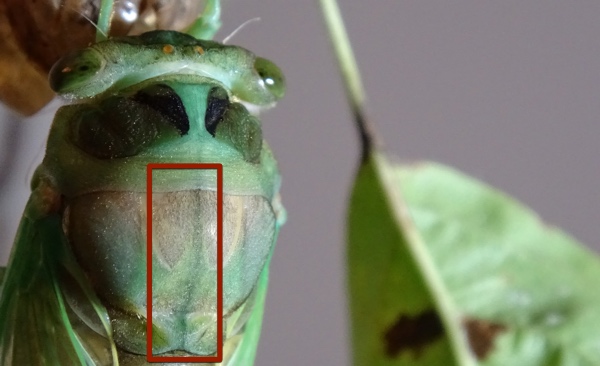

My guess, without reading the document, is that Megatibicen includes the larger North America Neotibicen species, including the “auletes group” (M. auletes, M. resh, M. figuratus, M. resonans), the “pronotalis group” (M. pronotalis, M. dealbatus, M. cultriformis) and the “dorsatus group” (M. dorsatus, M. tremulus), or a mix of these. M. auletes is the largest cicada in North America. “Mega” is the Greek word for “very large” or “great”. Word is that Kathy Hill and David Marshall also planned on describing a Megatibicen genus at one point, as well.

Whenever cicada names change it causes feelings of bemusement, discontentment, and discomfort amongst some cicada researchers and fans. I know I don’t like it because I have to update the names of cicadas in 100’s of places on this website ;). Some folks simply disagree with the folks writing the paper. Some people prefer former names because they sound nicer (e.g. N. chloromerus vs N. tibicen tibicen). Some people simply do not like change.

Related: Here’s my article on when Neotibicen & Hadoa were established from Tibicen.

1 Hill, et al. Molecular phylogenetics, diversification, and systematics of Tibicen Latreille 1825 and allied cicadas of the tribe Cryptotympanini, with three new genera and emphasis on species from the USA and Canada (Hemiptera: Auchenorrhyncha: Cicadidae) 2015, Zootaxa 3985 (2): 219—251.