People ask: why do periodical cicadas stay underground for 17 or 13 years?

There are three parts to this puzzle that people are interested in:

- How cicadas count the years as they go by.

- Why prime numbers? 13 and 17 are prime.

- Why is their life cycle so long? They are one of the longest living insects.

Cicadas likely don’t count like people do (“1,2,3,4…”) and you won’t find scratch marks inside the cell (where they live underground) of a Magicicada, marking off the years as they go by. However, there is a kind of counting going on, and a good paper to read on that topic is How 17-year cicadas keep track of time by Richard Karban, Carrie A. Black, and Steven A. Weinbaum. (Ecology Letters, (2000) Q : 253-256). By altering the seasonal cycles of trees they were able to make Magicicada emerge early, proving that cicadas “count” seasonal cycles, perhaps by monitoring the flow and quality of xylem sap, and not the passage of real time.

Why prime numbers, and why is the life cycle so long? This topic fascinates people. The general consensus is that the long, prime-numbered life-cycle makes it difficult for an above-ground animal predator to evolve to specifically predate them. Read Emergence of Prime Numbers as the Result of Evolutionary Strategy by Paulo R. A. Campos, Viviane M. de Oliveira, Ronaldo Giro, and Douglas S. Galva ̃o (PhysRevLett.93.098107) for more on this topic. An argument against that theory is that a fungus, Massospora cicadina, has evolved to attack periodical cicadas regardless of their life cycle. Of course, a fungus is not an animal. Maths are easy for fungi.

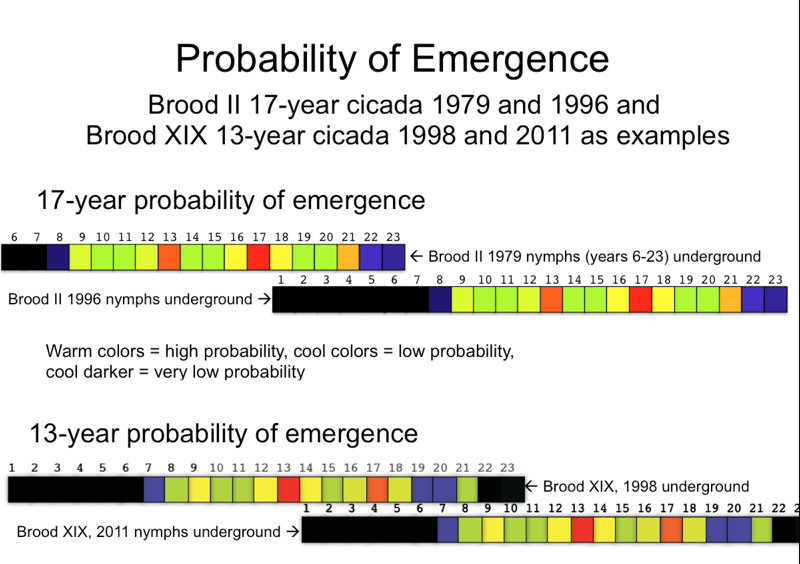

There are also questions about why there are 13 and 17 year life cycles, why a 4 year acceleration of a brood might occur1 and why Magicicada straggle.

1 This is a good place to start: Genetic Evidence For Assortative Mating Between 13-Year Cicadas And Sympatric”17-Year Cicadas With 13-Year Life Cycles” Provides Support For Allochronic Speciation by Chris Simon, et al, Evolution, 54(4), 2000, pp. 1326—1336.