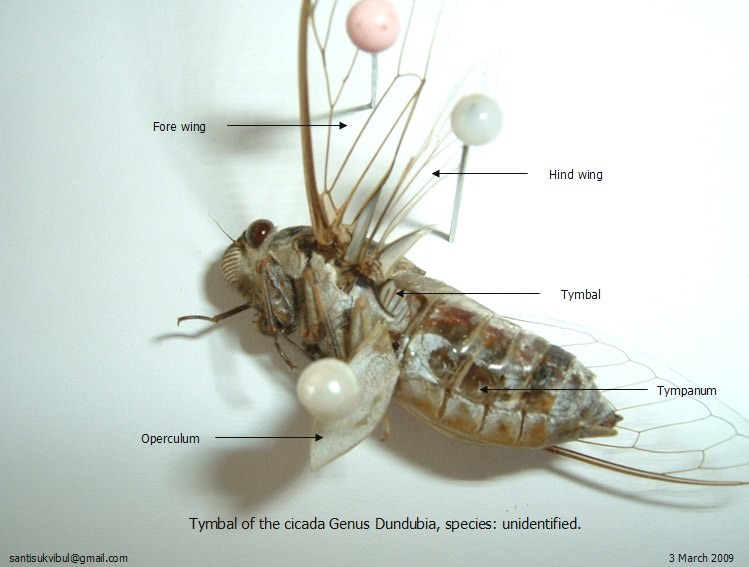

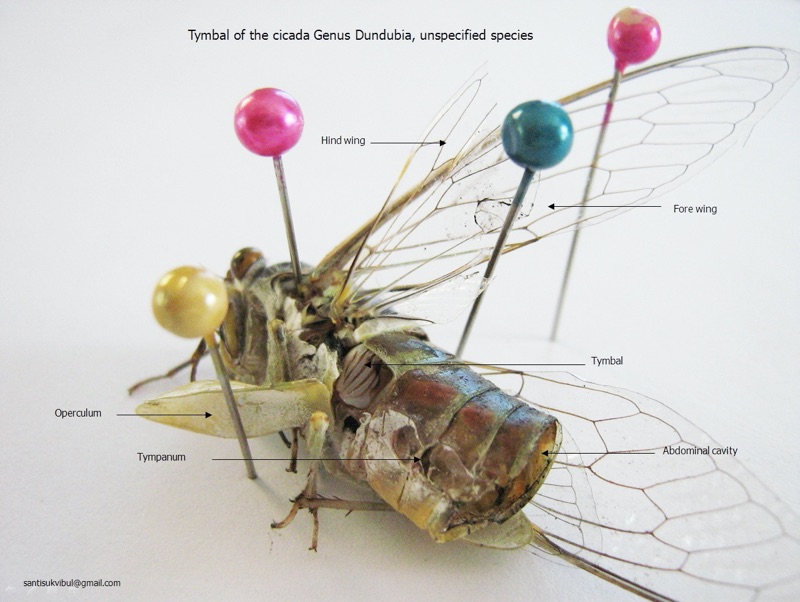

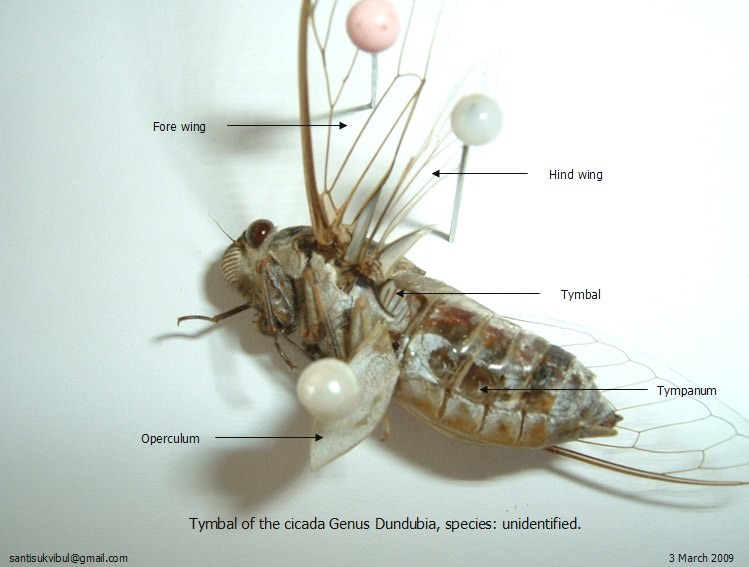

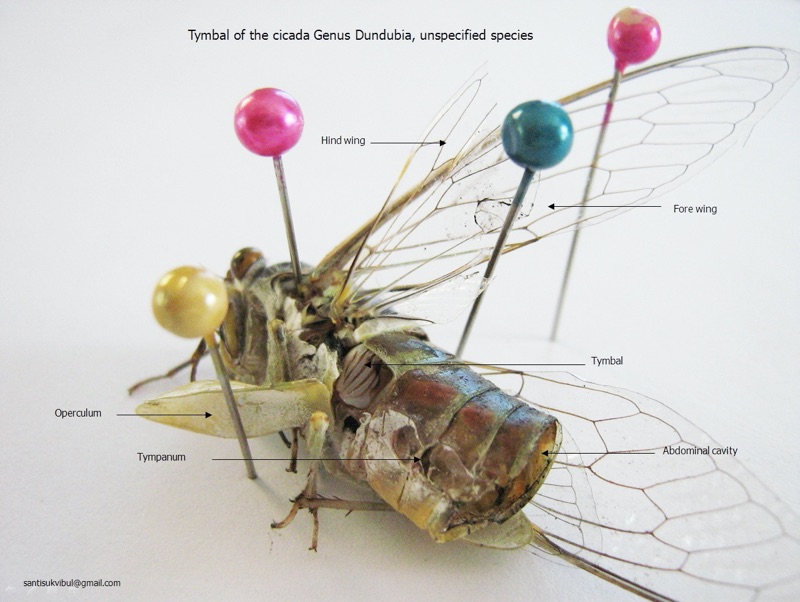

This photo points out the Tymbal (the organ that makes the cicada’s signature sound), the Tympanum (their hearing organ), the Operculum (which covers the Tympanum), and its wings.

This photo points out the Tymbal (the organ that makes the cicada’s signature sound), the Tympanum (their hearing organ), the Operculum (which covers the Tympanum), and its wings.

Cicadas are well known for the songs male cicadas make with their their tymbals, which are drum-like organs found in their abdomens.

Some female cicadas will also flick their wings to get the males attention. Watch this video where a male Magicicada is convinced that the snapping of fingers is a wing flick. Note: Magicicada males will also flick their wings once they become infected with the Massospora cicadina fungus (which removes their sex organs).

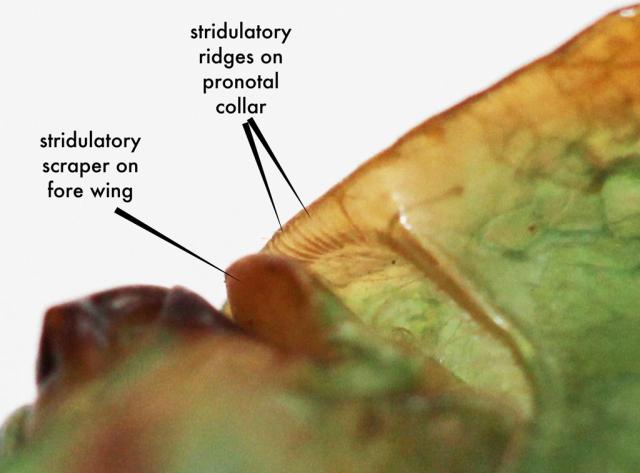

There is a third way some cicadas can make sounds. This method of creating a sound is unique to the Australian species Cyclochila australasiae (aka the Green Grocer and Masked Devil). These cicadas have stridulatory ridges on their pronotal collars (the collar shaped structure at the back of their head), and a stridulatory scraper on their fore wing.

From M. S. MOULDS, 2012, A review of the genera of Australian cicadas (Hemiptera: Cicadoidea). Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand. p84:

Cyclochila is unique among the Cicadoidea in possessing a stridulatory file on the underside of the lateral angles of the pronotal collar that interacts with a scraper on the fore wing base (Fig. 132). Rubbed together these produce low audible sound in hand-held specimens (K. Hill, pers. comm.), the purpose of which is for sexual com- munication at close quarters (J. Kentwell and B. Fryz, pers. comm.)

Here is a photo of these structures:

The location of these structures is right about where the blue pin is in this photo:

Update:

Tim McNary of the Bibliography of the Cicadoidea website, let us know that Clidophleps cicadas are also able to create should using a stridulatory structure. Clidophleps is a genus of cicada that can be found in California, Nevada, Arizona, and I assume adjacent parts of Mexico. Clidophleps differs from Cyclochila in that the stridulatory structure is on its mesonotum, and not its pronotal collar.

Photo courtesy of Tim McNary:

The Simon Lab is dedicated to the study of cicadas, in particular, periodical cicadas.

One of the things they study is the development of cicada nymphs while they are underground.

They need your help to collect cicada nymph specimens. You would dig for them, and if you find them, mail them to the Simon Lab. The nymphs will be used for valuable scientific study, so the loss of a few from your yard will not be in vain.

If you are interested in participating in cicada nymph research, visit The Simon Lab Nymph Tracking Project page for more information. You must have had periodical cicadas on your property in past 13 or 17 years to find the nymphs — not including the Brood II area, since those nymphs came out of the ground this year.

I didn’t see any nymphs emerge and undergo ecdysis tonight, but I did find plenty of cicada chimneys and nymphs trapped under slates.

Cicadas build chimneys above their holes, typically after it rains a lot and the soil becomes soft. The chimneys help keep water from rushing into their holes, and they keep ants and other menaces out.

A good place to find cicada nymphs is under backyard slates (or similar objects that cover the ground). Flip over your slates and you might find a nymph tunneling their ways to the side of the slate.

Brood II 17 Year Cicada Nymph trapped under a slate from Cicada Mania on Vimeo.

When a cicada sheds its nymphal skin, revealing its adult form, we call it ecdysis. You probably call it molting, and that’s just fine.

Here are a bunch of videos of cicadas moulting:

Here is a Magicicada nymph molting (the 17-year variety) by Roy Troutman:

Magicicada nymph molting from Roy Troutman on Vimeo.

Annual cicada molting to an adult by Roy:

Annual cicada molting to an adult from Roy Troutman on Vimeo.

Here is Tibicen moulting by blackpawphoto (YouTube Link):

Here is a video of a Japanese cicada, the Terpnosia nigricosta, moulting by AntoSan09 (YouTube Link):

I made this page for two reasons: 1) to point out insects and other animals that people commonly confuse with cicadas, and 2) list people, places and things named "cicada" that clearly are not cicadas.

By the way, if you’re looking for places to Identify insects that are not cicadas, try Bug Guide and What’s that Bug.

Are cicadas locusts? No, but people call them locusts, and have since the 1600’s.

Grasshoppers, Crickets and Katydids are often confused with cicadas because they are relatively large, singing insects. There are many differences between cicadas and Orthopterans, but the easiest way to tell them apart is Orthopterans have huge hind legs.

The Songs of Insects has song samples of grasshoppers, katydids, crickets and cicadas — listen and compare.

Learn more about insects belonging to the Order Orthoptera.

True locusts are

Locust:

17-year cicada:

People call periodical Magicicada cicadas "locusts" because they emerge in massive numbers like true locusts. Unlike true locusts — which will chew, eat and destroy virtually all vegetation they come across — most cicadas only cause damage to weaker tree branches when they lay their eggs. When true locusts come to town, your family might starve and die (because the locusts ate all your food). When cicadas come to town, your maple tree gets a few branches of brown leaves. Big difference.

Learn more about Grasshoppers on BugGuide.

Katydids get confused with cicadas for both the way they look and for the sounds they make. Some key differences: katydids usually have wings that look like green leaves, long antennae, and large hind legs for jumping. Most of the time you year an insect at night, it’s either a cricket or a katydid.

Photo by USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Laboratory.

Learn more about Katydids on BugGuide.

Learn about North American Katydids on orthsoc.org

Crickets don’t look like cicadas, but they do make sounds. Most of the time you year an insect at night, it’s either a cricket or a katydid.

Photo by USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Laboratory.

Learn more about crickets on BugGuide.

Learn about North American Crickets on orthsoc.org

Sphinx Moths are confused for cicadas because, at a glance, they have a similar shape. Learn more about Sphinx moths.

Planthoppers (Infraorder Fulgoromorpha), Froghoppers (Infraorder Cicadomorpha > Superfamily Cercopoidea), and Cicadelloidea (Infraorder Cicadomorpha > Superfamily Membracoidea ) are often mistaken for cicadas (Infraorder Cicadomorpha > Superfamily Cicadoidea) because they share the same Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order and Suborder — and they look a lot alike. The big difference is cicadas sing, while other members of Auchenorrhyncha do not sing.

Photos by USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Laboratory.

Learn more about the other members of the Suborder Auchenorrhyncha.

NO, cicadas are not June Bugs. Many people confuse June Bug larvae for cicada larvae.

“I dug up a white grub in my backyard. Is it a cicada?”

Maybe. Just about every insect goes through a larval phase, and they pretty much all look alike to the novice. Unlike beetle larvae, cicada larvae or nymphs are not long-bodied like grubs. Long larvae = beetle larvae.

An example of a young cicada nymph unearthed from the ground. Note how its body is white, but it doesn’t have the Cheetos/worm-like body of a beetle grub:

Frog calls are often mistaken for cicada song, particularly at night.

Bird calls can be mistaken for cicada song. Some birds that can mimic sounds, such as Lyrebirds, Mockingbirds, and Psittaciformes (Parrots) could conceivably mimic cicada sounds.

No one would confuse a horse with a cicada (visually and audibly speaking), but there was a famous horse named cicada.

These are people (in the form of Bands), places and things named cicada. They often show up on Flickr, Twitter, eBay or Amazon, when I’m searching for cicada insects. It is awesome that people name stuff after cicadas (but it can be annoying when you’re searching for cicada insects, and other stuff shows up).

There are many bands with "cicada" in their name. These show up a lot on eBay and Twitter. Here is a partial list:

There are many albums named Cicada as well, such as Cicada by Cat Scientist. That one comes up a lot in ebay.

These places show up on twitter, and when I search for cicada photos on Flickr.

Here’s a list of other things that often show up in eBay, Twitter and Amazon.

Blue cicadas. Did you know they exist? They do… at least in Australia.

What’s That Bug recently posted a photo of a blue Bladder Cicada from Australia (Cystosoma saundersii). It’s a great find. Cystosoma saundersii are typically green.

Then there is the Blue Moon blue colored morph of Cyclochila australasiae:

Photo by David Emery

Cyclochila australasiae come in many colors, but the most common color is green. “Blue Moon” is a good nickname for these cicadas because they are rare and only found, idiomatically speaking, “once in a Blue Moon”.

So, why are some cicadas blue, when their species is typically green? Here is a quote from the paper Blue, red, and yellow insects by B. G. BENNETT, Entomology Division, DSIR, Private Bag, Auckland, New Zealand:

The colours of insects are often due to a complex mixture of pigments, some of which

are concentrated from their diet. These are carotenoids, flavonoids, and anthraquinones, and some are porphyrins made from the breakdown of plant chlorophyll. Insectoverdin is a common green pigment produced by a mixture of blue and yellow compounds. The blue is tetrapyrrole, but sometimes an anthocyanin, and the yellow is a carotenoid.

Blue + yellow = green. If the yellow is missing, you get a blue cicada. I heard that, at least in the case of the Cyclochila australasiae, the blue cicadas are typically females. Perhaps something related to genetics or behavior of the females leads to an inability to process the caroteniods ingested along with their diet (tree fluids). I’m not sure, but it’s a topic that fascinates me, so I’ll continue to look into it.

Apparently cicadas serenaded the dinosaurs! Entomologist and Mount St. Joseph professor Gene Kritsky shared the news today that cicadas lived as long as 110 million years ago during the Cretaceous period.

A quote from a press release:

New research has documented that cicadas, those noisy insects that sing during the dog days of summer, have been screaming since the time of the dinosaurs.

A fossil of the oldest definitive cicada to be discovered was described by George Poinar, Jr., Ph.D., professor of zoology at Oregon State University and Gene Kritsky, Ph.D., professor of biology, at the College of Mount St. Joseph in Cincinnati. The cicada, measuring 1.26 mm in length, was named Burmacicada protera.

Read the full Press Release on the MSJ website.

Here is a photo of the ancient Burmacicada protera cicada nymph trapped in amber. Photo credit: George Poinar, Jr., Ph.D.

It looks a lot like a modern-day first-instar cicada nymph:

Photo by Roy Troutman.

Update: Here’s a video news story about Gene’s fossil find.

I need a step-up my fossil collecting hobby. It looks like there’s some places in New Jersey to find fossils. Maybe I’ll find a cicada.

The White-eyed cicada contest is complete!

I had ten “I Love Cicada” pins sitting in a bag in my office. Ten people found a white-eyed cicada, sent me a photo and won “I Love Cicadas pins”!

Our first pin winner is Joey Simmons of Nashville, TN:

Our second winner is Meagan Lang of Nashville, TN:

Our third winner is Serena Cochrane of Gerald MO:

Our fourth winner is Melissa Han of Nashville TN:

Our fifth winners are Jane and Evan Skinner of Troy MO:

Our sixth winner is Phyllis Rice of Poplar Bluff MO:

Our seventh winner is Jack Willey of Nashville TV:

Our eighth winner is Chris Lowry of Nashville TN:

Our ninth winner is Nathan Voss of Spring Hill TN :

Our tenth and final winner is Paul Stuve of Columbia, MO:

Here’s the prize pins:

Most of the periodical cicadas you’ll see have red or reddish-orange eyes. A very small number, however, have white, blue, or yellow eyes. Some even have amazing multi-colored eyes. Have you seen any white eyed periodical cicadas yet? Be on the lookout for them, and make sure you take a photo or video when you see one. Have a contest with your friends and family to see who can find the first white or blue-eyed cicada. If you have a TV station, radio show or a local website, you could have a contest for who can find the first white eyed cicada. I personally have only found one white eyed cicada (video below), so I have to guess that the odds are at least one in 10,000.

Here’s a photo of a white eyed Magicicada cicada Roy Troutman found back in 2004:

Roy took a photo of a blue-eyed cicada, and I made a t-shirt from the image (I use the mug version for my morning coffee).

This is a video of white eyed cicada I recorded back in 2007: