The point of this article is that you should be on the alert for Magicicada periodical cicadas, no matter what year it is, and if you see or hear them, report them.

Stragglers, in terms of cicadas, are periodical cicadas that emerge in years prior to (precursors) or after their brood is expected to emerge. Most often, 17 year cicada stragglers emerge four years prior to their expected emergence date — but it is possible for periodical cicadas to emerge between 8 years earlier and 4 years later than expected. Read more about cicada stragglers.

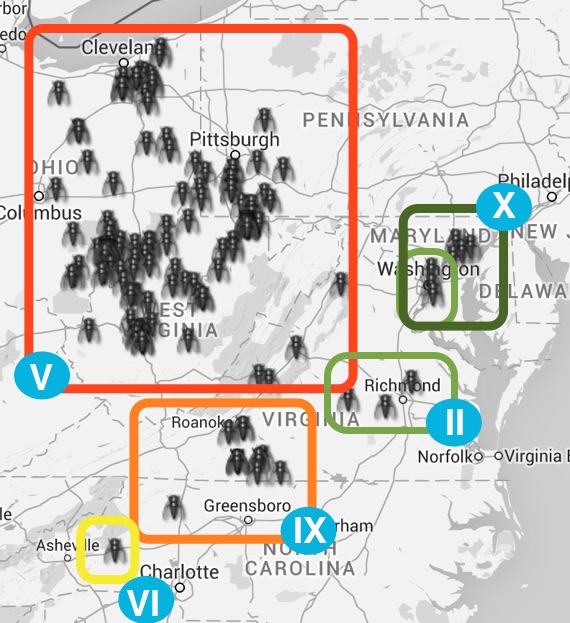

This year (2016) Brood IX stragglers should emerge in southern West Virginia, western Virginia and the north-middle part of North Carolina that connects with western Virginia. See a map here.

Looking at the live map on Cicadas @ UCONN (formerly Magicicada.org), it is obvious that most reports come from Brood V and stragglers appear to be emerging in the Brood IX & VI areas as expected — however, there are a fair number of reports in the Brood II and X areas, which is odd.

- Red: Brood V

- Orange: Brood IX, 4 years early (most probable)

- Yellow: Brood VI, 1 year early (probable)

- Green: Brood II, 3 years late (rare, but possible)

- Dark Green: Brood X, 5 years early (rare, but possible)

As stated before, it is common for periodical cicadas to emerge 4 years early, but 5 years early is rare. So why Brood X be stragglers this year? That requires a little more thought.

Now we enter the realm of conjecture…

Rick Karban in the paper How 17-year cicadas keep track of time1 demonstrated how you can get cicadas to emerge earlier than expected if you alter the seasonal cycles of their host trees. Make the tree experience two cycles in one year, the cicadas will read this as “two years have passed” and they’ll emerge a year earlier. So, in the case of Brood X stragglers, it could be that their host trees experienced weather fluctuations that caused them to do something that signaled the cicadas that 2 years had passed. Add the 4 years they would likely straggle + 1 year caused by fluctuations from the host tree, and that makes for a 5 year straggler.

The other day wethertrends360 posted this on their facebook page:

Growing Degree Days tell us why the Northeast had such an early surge in plant growth but then slowed. From late February to early April temperatures were near record warm in the Northeast with the 2nd most Growing Degree Days (GDD) in 25 years (chart/map left). This allowed plants to emerge way too early and then the freezes came!

Perhaps this early surge in plant growth, then a freeze, then growth again seemed like two years had passed to some cicadas. Perhaps.

1 How 17-year cicadas keep track of time, Richard Karban, Carrie A. Black1 and Steven A. Weinbaum, Ecology Letters (2000) 3 : 253-256.