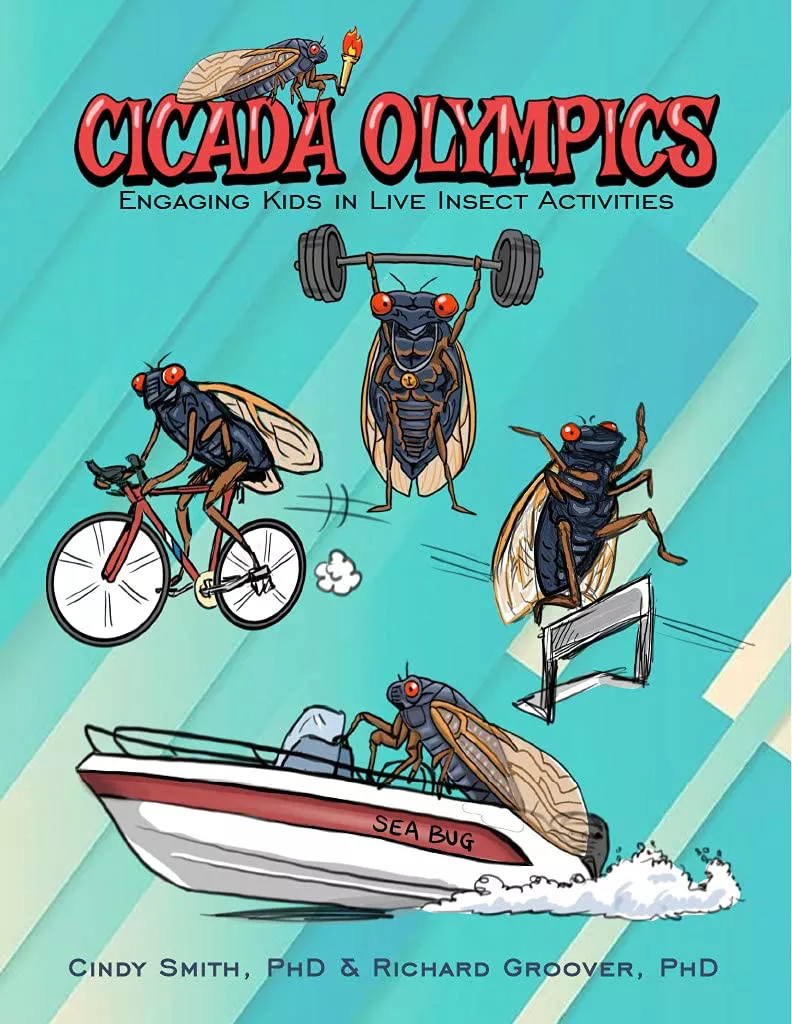

Hey! There’s a new cicada book out for Kids. Looks fun. The Cicada Olympics: Engaging Kids in Live Insect Activities. by Cynthia ‘Cindy’ Smith, Ph.D. & Richard Grover. It is available on Kindle or Paperback from Amazon.

About the book:

With two periodical broods set to emerge this spring, now is the perfect time to start planning educational events and activities that celebrate this fascinating natural phenomenon. The Cicada Olympics book is packed with 14 easy-to-implement engaging activities, student worksheets you may copy, and sample letters to parents, providing you with everything you need to organize successful cicada events at parks, schools, neighborhoods and communities. From interactive games and races to exoskeleton exploration, these activities are designed to spark curiosity, promote learning, and foster deep appreciation for these gentle giants.

The Cicada Olympics book offers a comprehensive toolkit designed to help you create a fun, informative and memorable experience for learners of all ages. 62 pages.

An interview with the author:

1) Why did you decide to create a book about periodical cicadas? Please tell us more about the book.

In 2004 I hosted a highly successful school Cicada Olympics event where kids rotated through 12 activity stations with their own personal cicada. It was magical! To start, each child decorated a small wire-handled takeout food container and then selected a male or female cicada, which they named and carried to all the events. Kids were laughing, cheering, comparing with friends and learning. I was encouraged by the teachers, parents and volunteers to capture the activities in a book so that that other parents, educators and youth leaders could easily recreate them. The book details all the materials needed and ways to teach, even if you’re terrified of bugs. For example, a STEM engineering challenge is detailed, where kids build a small boat which they ‘race’ across a kiddee pool with their cicada as captain.

Periodical Cicadas are the best teaching tools. They’re big, slow, they don’t bite and they mostly stay put while you hold them. Kids tell me that if you stare into their pointy faces, they kind of look like they’re smiling. My goal in writing the book was to help youth leaders, educators, parents, and guardians to easily put on an educational event or engage children in individual activities with cicadas. In addition to examining anatomy, mimicking calls with kazoos and building pyramids out of exoskeletons, integrating cicadas into learning activities is an awesome way to help kids become very comfortable with insects, retain a great deal of life history knowledge and have more awareness about insects’ roles in the environment.

2) How did you become interested in periodical cicadas?

Since I was a kid, I have been fascinated with insect and animal behavior. I remember as a 2nd grader, collecting loads of ladybugs and moths in a metal coffee can and (much to my mother’s horror), releasing them in my bedroom to show her how I ‘trained’ them all to fly to the windows. For my master’s degree, I focused on bird behavior, working on projects ranging from seagull feeding behavior in landfills to bowerbird displays in Australia.

I love the intrigue of the periodical cicada life cycle. What exactly are they doing underground for 13 or 17 years? Just sucking on tree roots seems rather boring to me. Are they communicating with each other? “Hey, are you going to the big party in the trees? I can’t wait!” Do they interact with the grubs and centipedes underground? Do they ever sneak up to the surface years too early, check out the aboveground scene and then go back down to wait? I have observed stragglers coming out in their ‘wrong’ year and quickly getting carried away by birds.

3) Which was the first cicada Brood you experienced, and where did you experience it?

Brood IV near Manhattan, Kansas while I was attending Kansas State University working on my Wildlife Biology degree. I’ve experienced Brood X in Northern VA in 2004 and 2021.

One evening in May 2013 when Brood II emerged in the woods near my home in Virginia, I sat, my back against an old beech tree, as 100s of nymphs crawled out of their soil tunnels. Nymphs crawled up my shoes, up my legs and when they reached my bent knees – the highest point, they turned around a few times and then crawled back down to the ground to find a better ‘tree’.

When I brought neighborhood kids to witness the emergence, at first, they were squeamish and squealing as pairs of tiny toes touched and tickled their legs. Once the children got comfortable and noticed how determined the cicadas were to walk upwards, (and that the insects did not care one iota about them), the wonder questions flowed like floodwaters: Do you think he likes me? How high will they climb? Are their red eyes full of blood? Can they see me? Can I take them home as a pet? That would hurt me if my back split open, does it hurt when they molt? Can they still breath when they molt? What are those white hairs in the shells? etc…

Emotional experiences like this are unforgettable.

4) Are you interested in other types of cicadas? Are you interested in other types of insects?

Yes! I always anticipate the songs of the annual cicadas. I love how they crank up the volume on hot summer days. I’m very interested in insect-plant associations. I strategically plant flowers in my yard for insect observation and photography. Today for example, I watched small bees (Ceratina species) clearing out tunnels in last year’s elderberry stems.

5) How are insects and other smaller creatures (frogs, turtles, birds) useful in engaging and educating young people about their local environment?

Experiences with live organisms are memorable. Last week at one of my environmental education programs, 7th graders were collecting data on water chemistry in a stream. While testing the water, they spotted a dragonfly nymph molting on a stem. Immediately, all the children crowed around to watch. When they met up later with their teachers, none of them discussed the amount of dissolved oxygen they recorded, but all of them chattered about the bald eagle that flew by, how the dragonfly cracked out of its exoskeleton and how cute the baby turtle was that they held.

When I train K12 teachers and ask about their most memorable science experiences, most smile and share stories about farm trips, raising rabbits and chicks, finding a box turtle, holding a snake and visiting public aquariums.

6) How can parents, guardians, and teachers educate young people about insects and their local environment? What types of resources should they look for?

Take your kids outside and often. Examine the different plants on your playground, in your yard and under your feet. Visit parks, nature preserves, wooded areas, meadows, streams, and the ocean. Join tours with naturalists. Visit the same natural spaces again and again and notice what has changed. Scheduling enough time to listen to insects and birds and watch their behavior. Encourage your kids to ask questions and wonder. You don’t have to have answers for them. The most important thing is to value their observations skills, honor their discoveries and ask them questions about what they are seeing, such as: How do you think this plant/insect/animal got here? What might it have looked like last week? What might it look like next week? Do you think anything eats this? This will build critical thinking skills.

Identification apps like iNaturalist, Seek, and Merlin are good, but… frequently, I see nature conversations end the second someone identifies the plant or insect. Skip the apps for a while and let children observe, describe and sketch what they see without checking to see if they are ‘right’.

7) Tell us about your role as professor of Environmental Science & Policy?

As instructional faculty at George Mason University, I teach undergrad and graduate courses covering topics such as Stream Bioassessments, Heat Island Impacts, Ecology of Climate Change, Sustainability, product Life Cycle Assessments and more. Because Mason is located close to Washington DC, I host members of congress, state delegates and lobbyists into my classes to give students authentic experiences with policymakers focused on environmental issues.

8) Tell us how Environmental Science & Policy matters to the community (“everyday people”):

Much of what the public hears about the environment and climate is doom and gloom which can lead to eco-anxiety. I like to highlight success stories, empower my students to select problems they want to solve, and to understand all stakeholder viewpoints, because environmental issues are rarely two-sided. In our local neighborhoods for example, native plant proponents want residents to reduce their lawns, plant natives to encourage more insects and let the oak-hickory forest return. But opponents ask, “Where will the kids and dogs play? What if my family is allergic to bees?” All stakeholders have valid points. Crafting policies that support all residents go a long way in building positive communities.

9) Tell us about your role as Outreach Director for the Potomac Environmental Research & Education Center (PEREC):

PEREC is a research Center at George Mason University. My colleagues’ research topics span aquatic and fisheries ecology, microbiology, invertebrate invasions, environmental chemistry, sustainability and coral reef diseases. My role is to translate their research into hands-on public programs, exhibits and tours. With my part-time student staff we deliver ~ 60 days of watershed education programs directly reaching over 7000 youth per year. I also train 100s of K12 teachers on ways of Teaching Kids Outside, while still meeting their required learning objectives.

10) What is one (or more) thing the average person can do to help improve the health of their local environment?

Consider outdoor spaces in neighborhoods as essential ecosystems. Plant, plant, plant! Add native plants, shrubs and trees to your yard or plant in pots if you have limited outdoor spaces. These will attract insects, which in turn feed birds and pollinate plants.

My son, for example, lives in a concrete urban city where it’s challenging to have access to outdoor planting spaces. His neighbor drops routinely seeds into alleyway crevices, next to dumpsters, and along building/sidewalk cracks. Sunflowers, corn, as well as native and annual flowers pop up randomly throughout this urban area. You can build up biodiversity almost anywhere.

11) Do organizations like the PEREC communicate and share ideas with similar organizations around the country and world.

Of course! Our faculty all have webpages and social media sites.

Your audience can follow my research team at:

Instagram: @perec_gmu

X (Twitter): @PEREC_GMU

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/PerecGMU/

You can follow me on:

Instagram: @drcindysmith

X (Twitter): @cindyloohoo9

My Website: https://www.drcindysmith.com/

LinkedIn: LinkedIn

Thank you for checking out my book, The Cicada Olympics – Engaging Kids in Live Insect Activities

Description of the book from Amazon:

This book, by Cindy Smith, Ph.D. and Richard Groover, Ph.D., will equip you with age-appropriate information to make this a fun learning opportunity for your children. The authors have made the learning activities streamlined and easy to implement for individuals and groups. Within these pages, you’ll find: 13 fun cicada activities with instructions and materials list, parent and volunteer information, cicada jokes, pictures, and online resources